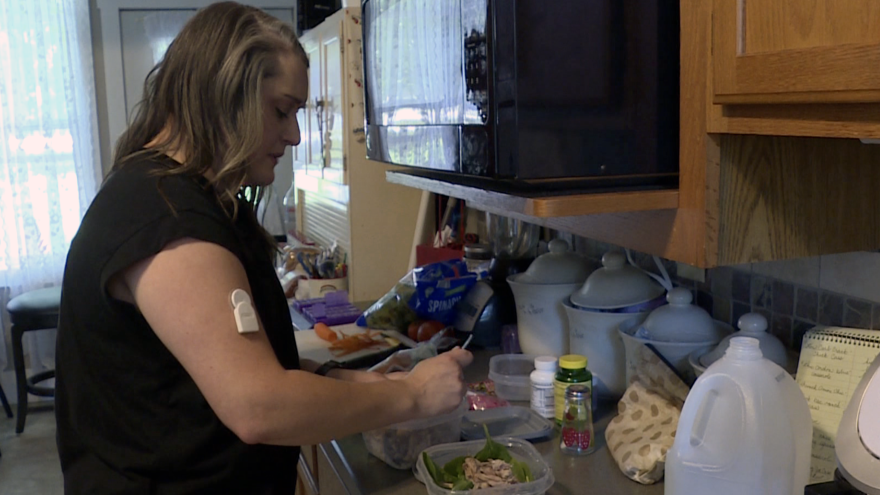

Molly King was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was 18. Her body can’t create insulin, so she’s spent every day since navigating her insulin regimen.

Not all diabetics take insulin, but for those who do, the medicine is the difference between life and death. Insulin helps control blood sugar, and without it, people with diabetes can suffer serious medical problems including blindness, comas, or even death.

“Anytime I eat food of any kind, I have to inject myself with insulin,” said King, 30, a special education teacher who lives in Covington, a city in western Indiana.

King takes two forms of insulin to help control her blood sugar: one long-acting form she takes twice a day, and the short-acting form for when she eats. The types of insulin she takes hasn’t changed over the years, but the price of the medication has.

From 2010 to now, the price of her monthly insulin has skyrocketed from around $300 to over $1,000 a month. The financial burden became so much that she had to move back in with her parents just to afford her medication.

King’s story isn’t unique. The price of insulin has more than tripled in the past two decades; A one-month supply of Eli Lilly’s Humalog has jumped from $21 in 1996 to about $275 in 2019.

That’s why King, and many others, had some hope when Inflation Reduction Act talks began.

The $750 billion economic package that was signed into law Aug. 16 creates a $35 insulin co-pay cap for people on Medicare, starting in 2023. Biden touted the package as a big win for Americans, but many who rely on insulin were disappointed by the final product.

About 37 million Americans – or 1 in 10 people – have diabetes.

“This bill helps a minority of people, it does not help the majority of people with insulin needs,” King said.

Some lawmakers rejected the Inflation Reduction Act

The initial version of the Inflation Reduction Act called for a similar, $35 co-pay cap for people also on private insurance. That would’ve been huge for King.

But most Senate Republicans voted against the cap, including Indiana’s.

Both Sens. Todd Young and Mike Braun declined interview requests for this story, but a spokesperson for Braun said in an email that the senator voted against the cap because it violated Senate budget rules.

“Had that vote passed, it would have overruled the Senate parliamentarian and expanded the scope of the budget reconciliation process to allow for price controls on private companies,” the spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said Braun would continue pushing his bipartisan bill to help expand access to low-cost, generic forms of medicines and stop pharmaceutical companies from stifling competition through “parking.”

One of the ways brand-name pharmaceutical companies maintain control of the market is by agreeing to not sue a generic drug company if it agrees to delay production of the generic drug.

Shaina Kasper, policy manager for T1International, a nonprofit that advocates for affordable insulin access, said “parking” has become a major issue for all drugs, but particularly insulin affordability – especially considering three companies produce 90 percent of the global supply of insulin: Sanofi, Novo Nordisk and Indianapolis-based Eli Lilly.

“They have this captive market, so they can charge whatever they want and rake in extraordinary profits,” Kasper said.

The companies have said their prices are due to the complicated medical landscape in the U.S., and people generally don’t have to pay the full list price.

In an emailed statement, an Eli Lilly spokesperson said the company was in favor of the private, $35 co-pay cap that failed in the Senate. They also said anyone can buy their monthly prescription of insulin for no more than $35 through its discount programs.

“Our solutions have helped lower the average monthly out-of-pocket cost for Lilly insulin to $21.80, a 44 percent decline over the past five years,” the spokesperson said.

Co-pay caps help some, but leave others out

Advocates for insulin cost control say a co-pay cap for private insurance would be another step in the right direction.

But even that is still far from what Kasper’s group is calling for: a true cap on insulin prices.

While an expanded co-pay cap would help, uninsured people – who often need the most financial assistance – would still be left to pay full prices, she said.

“One out of four patients with diabetes has rationed insulin due to cost,” Kasper said. “And we think that number is probably even an undercount because a lot of folks don’t recognize that what they’re doing is rationing.”

King, the schoolteacher, knows the dangers of rationing insulin: Years back, she experienced diabetic ketoacidosis after she tried to make her medicine last, and ended up in the hospital for a week.

“I was completely unconscious,” she said. “I don’t remember like six days of my life.”

And while discount programs such as Lilly’s are available, not everyone is able to access all of their benefits.

Hena Shah, a nurse practitioner with IU Health Southern Indiana Physicians who works with diabetes patients, said she has seen patients get insulin from other countries at a cheaper price.

“If you are not already established with a primary care provider or if you’re not already seeing a diabetes specialist elsewhere, [discount programs are] difficult to access because most people can’t navigate those resources on their own,” Shah said.

If patients struggle to access affordable insulin, Shah said she works with them to navigate patient assistance programs online or use resources like GoodRx.com to figure out where they can get the medication with the lowest out-of-pocket cost.

King isn’t on a Lilly brand of insulin, and she’s exhausted the discount options available to her. So she’ll continue paying $1,000 a month for her medication.

She’s happy to see Congress take some action on insulin prices, but said it’s a long way from making a difference for people in her situation.

“[We’re] being majorly penalized by our health care system because our bodies don’t make insulin,” King said. “We’re being charged this astronomical price simply for an organ not working.”

The American Diabetes Association says it plans to continue advocating for relief this fall, including capping monthly insulin costs for more patients.

This story comes from Indiana Public Media, in collaboration with Side Effects Public Media. Follow Mitch on Twitter: @ByMitchLegan.