Updated June 24 at 8:30 a.m.

This story contains graphic descriptions of an abortion and mentions suicide.

Renee Chelian lived through a time when it was illegal to have an abortion.

Her parents helped her get the procedure in 1966, seven years before the landmark Supreme Court case, Roe v. Wade. Chelian was 15 years old, pregnant and terrified.

"They explained to me that I wouldn't be pregnant anymore, but that it could be dangerous because it was illegal,” Chelian said, “which meant we couldn't tell anybody.”

Chelian rode in a stranger’s car to a dirty warehouse in Detroit for the operation. She was blindfolded so that if she were ever questioned by police, she wouldn’t be able to say where it happened.

At the warehouse, a doctor stuffed gauze into her uterus to trigger a miscarriage.

Chelian ultimately needed a second procedure at a different warehouse before she finally passed the pregnancy in her family's bathroom.

"Somebody came and picked [the fetus] up,” she said. “And my dad came home with all of my siblings and came in to see how I was doing and said to me: 'We will never speak of this again.'"

After decades of silence, Chelian, now 71, is telling her story publicly to help people understand the desperation and danger that could come with history repeating itself.

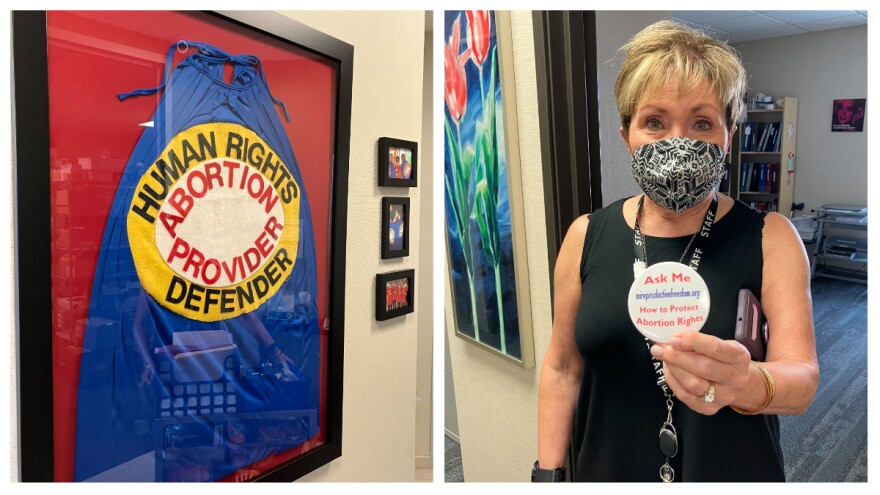

Today, Chelian and her two daughters run the Northland Family Planning Centers, a group of clinics that provide abortion services in the Detroit and Ann Arbor suburbs. Chelian is clear-eyed about what could be ahead if the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade: Her clinics could close, or conversely, if the state preserves the right to abortions, could be overwhelmed with pregnant patients coming from other states.

“I don't think political people have really thought about what kind of health care crisis there's going to be in this country,“ Chelian said. “We're going to see women self-inducing. We are going to see people breaking the law and the criminalization of women. We're going to see children suffer. Half of our patients already have kids, and they tell us the reason for their abortion is to take care of the children that they have now.”

Michigan is one of more than 20 states with a law on the books that would outlaw nearly all abortions if Roe falls.

That threat has Democratic officials and ordinary citizens in this Midwestern swing state locking arms to keep abortion legal.

The battle is political and personal.

“As a mom of young women, the thought that my girls might have fewer rights than I’ve had my whole life is devastating and infuriating,” said Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. “And that’s a part of what keeps me staying focused on this space.”

Michigan officials and activists have mobilized around a tier of strategies: in the courts, on the campaign trail and at the ballot box this November.

Planned Parenthood has challenged the state’s 1931 ban on abortion. That plan has had the most impact so far, with a judge issuing a preliminary injunction in May to block the ban from going into effect if Roe falls. Still, it's far from a permanent fix.

Whitmer has her own lawsuit pending. It asks the state supreme court to determine if the 1931 ban violates the state’s constitution. The governor is running for a second term and made reproductive rights a central pillar of her campaign.

If legal steps fail and the ban is reinstated, providing abortion would again become a felony in Michigan, with exceptions only to save the pregnant person's life. State Attorney General Dana Nessel, who also is running for re-election, has said she would not prosecute any doctors for performing the procedure, nor would she defend the ban in court.

“If I'm your attorney general, I will not enforce those laws,” Nessel said. “It's prosecutorial discretion. I don't have to enforce those laws.”

Michigan’s governor is determined, but realistic.

“We've pursued this kind of three-pronged strategy because we don't know which one might be successful,” Whitmer said. “We don't know if any of them will. And I think that's why this is such a stark, kind of scary, confusing moment.”

Many abortion rights advocates like Renee Chelian feel strongly that losing is not an option.

“We have to be a beacon for other states and give them a roadmap," she said.

Last spring, Chelian joined tens of thousands of volunteers in Michigan in an effort to gather 425,000 signatures to put a constitutional amendment on the November ballot. If they meet the signature threshold in the next few weeks, and convince a majority of voters to pass the amendment, the Michigan Right to Reproductive Freedom Initiative would create a state constitutional right to reproductive choice.

The initiative is widely seen as the best chance Michigan has to advance reproductive rights. It would apply to abortion and an array of reproductive health services like birth control and miscarriage management. A constitutional amendment would be harder for a future governor or legislature to overturn compared to a change in the law or a lawsuit ruling.

Residents are tuned in to the issue. In a recent poll of registered Michigan voters by the Detroit Chamber of Commerce, respondents listed abortion as one of their top three concerns.

There is a tough and expensive battle ahead in many states. Voters in Michigan and Vermont will consider constitutional amendments to protect abortion rights. Kansas, Kentucky and Montana are asking voters to amend their constitutions or affirm there is no legal right to an abortion in those states.

As for Chelian, she hopes beyond court rulings and the changing faces in political office, a direct vote would allow voters in her state to weigh in, one by one, on protecting abortion rights.

This story comes from the health policy podcast Tradeoffs, a partner of Side Effects Public Media. Alice Miranda Ollstein is a reporter at Politico and contributor to Tradeoffs, which ran a version of this story on June 23.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story said Renee Chelian kept silent about her abortion for more than 50 years. That was incorrect. Chelian started telling close friends and family about her abortion about 20 years after it happened and has only recently shared her story publicly.