Dr. Malaz Boustani, an Alzheimer’s specialist at Eskenazi Hospital in Indianapolis, wants to radically change the way mental health care is delivered. He believes the current state of the field is untenable, because so many are not getting the treatment they need. Only 41 percent of adults with a mental illness and 63 percent of adults with a severe mental illness received mental health services in the past year, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Boustani heads the new Sandra Eskenazi Center for Brain Care Innovation, which employs dedicated staff to coordinate care and check up on patients outside the hospital. Boustani's model for Alzheimer's care- which treats caregivers as well as patients - has had strong results at Eskenazi Hospital—and now Boustani is developing a new digital tool that to extend the reach of the program far beyond the hospital’s doors.

“I want my solution to be available for the person who questions a thousand times, ‘Can I afford a $5 co-payment?’” says Boustani. The solution he’s building is based on something that’s becoming more accessible and less expensive: artificial intelligence technology.

Boustani and a team of engineers are designing a digital tool that lets patients communicate with an avatar—a virtual human technology that interfaces with people. Imagine a combination of Siri and a character from SimCity or Second Life, connected to a database of information about mental illnesses. The idea is for the avatar to provide customized guidance to patients and caregivers, while at the same time collecting data to relay back to healthcare providers. They plan to have it up and running by 2018.

“You can think of the avatar as really an algorithm,” Boustani explains. “An algorithm that will be able to answer 90 percent of [patient and caregivers’] questions with very human-like features, 24/7, without asking a clinician to provide that answer.”

He says that with this technology in use, a healthcare provider could expand his or her patient base exponentially. Instead of spending the work day doing office visits with a handful of patients, a doctor might see one patient in person, complete five visits over video chat, exchange emails with ten patients, and still have time to review data for 50 more. He envisions its use not just for dementia, but for depression, anxiety,schizophrenia, and other conditions. Eventually, he says, Boustani wants this technology to be available to doctors and patients worldwide.

So what would the avatar do? Imagine, for example, you’re the caretaker for your mother, who has Alzheimer’s disease, says Boustani. You might tell your avatar “My mom has not been really listening to me, she's repeating the same question over and over.”

“The avatar can say: in people with Alzheimer's disease repetition is normal. These individuals do not have the ability to produce new memory. Any information stays with them within a minute or two minutes. Don't take it personally," Boustani says.

The avatar could have access to basic health information only, or it could "know" a whole lot more about a person, depending on the caregiver or patient’s preferences. Boustani wants the technology to be able to work a bit like a life coach, observing patterns in a person’s life, and offering suggestions.

“You should not be eating this now, it looks like you're a little bit depressed,” Boustani illustrates, speaking in the voice of the hypothetical avatar. “I would recommend you to go talk with Karim, because every time you talk with Karim, Karim kind of makes you happy and you stop thinking about eating.” Or, he says, if the avatar notices a patient’s cognitive skills have declined, it can recommend a brain game.

What might this virtual person actually look like? So far avatars have been screen-based. Lead engineer Karim Boustany (no relation to Dr. Boustani) says it’s too early to say for sure, but this avatar might be more lifelike. “In the future it might be a hologram that pops up in your living room and speaks with you just like another human being,” says Boustany.

Talking To Machines

The idea of using an avatar to help people with mental illness may seem counterintuitive. How could someone suffering through the isolating experience of dementia or severe depression benefit from talking with a computer program rather than a real human being?

A study conducted at last year at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies showed there may be some benefits to talking with a virtual therapist. Subjects sat at a computer and were interviewed about their lives and psychological wellbeing by a computer- simulated woman called “SimSensei.” Half of the subjects interacted with a fully automated computer program. For the other half, a researcher was controlling SimSensei. Some subjects were told they were interacting with an automated program when SimSensei was actually being controlled by a human, and vice versa.

In general, subjects who believed they were interacting with an automated program reported that they disclosed more information and were less worried about being judged. Whether Simsensei was actually automated or human-operated only affected ratings of the system’s usability.

Boustani says this study is an indication that avatars can be a useful tool. But he stresses that Eskenazi’s avatar will be just that -a tool - not a replacement for human-to-human therapy.

In addition to acting as a guide, the avatar would collect health data and relay it to a physician or therapist. “The technology will be very similar to how the echocardiogram takes care of your heart, how the brain CT scan helps take care of your brain,” says Boustani.

Data Collection

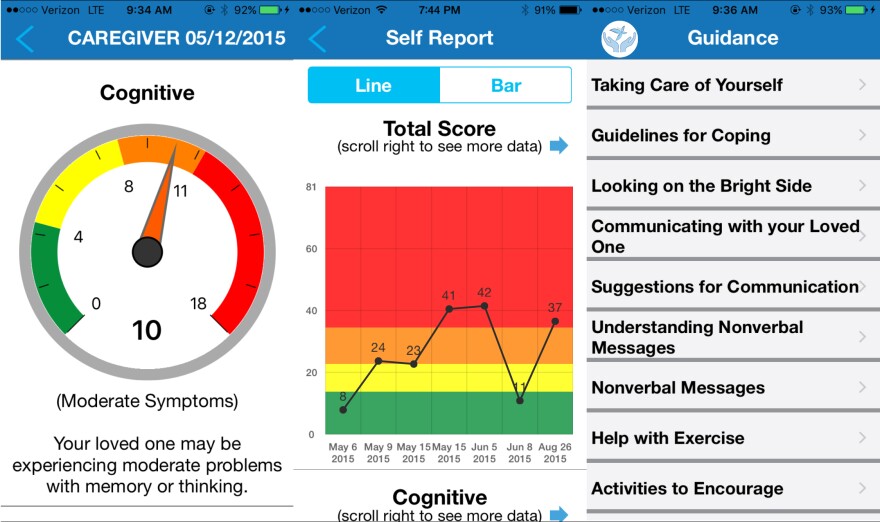

Today, Eskenazi Hospital uses a simpler tool to collect data on dementia patients – a needs assessment app. It’s designed for a caregiver to answer a series of multiple choice questions about quality of life, mood and physical symptoms for both caregiver and patient. At the end, it spits out a score, and links to some advice on how to cope. It’s helpful for doctor, patient and caregiver to track symptoms over time, but it’s a flat interaction, Boustani says. “We want more social interaction, more emotional interaction, more of a conversation,” he says. That’s what he wants the avatar to bring to the experience.

Cost Savings

Despite its high-tech nature, the avatar project shares a key goal with so many healthcare interventions these days – driving down costs. “We're going to keep out patients outside the hospital, outside of the emergency department,” says engineer Karim Boustany. “That results in a savings to the healthcare payer. "