Kim Manlove had been drinking since his teenage years. Two of his uncles were alcoholics. He overdid it at times, but for the most part he thought his habit was under control. He had a stable life, with a job in academia, a family and a house in the Indianapolis suburbs. But when Kim’s 16 year-old son David lost his life to alcohol and drug addiction, it drove Kim into pattern of heavy drinking and prescription drug abuse.

Grief over David's death pushed him deeper into his disease but ultimately was the key to his recovery and would change the way he lived his life.

Losing a child

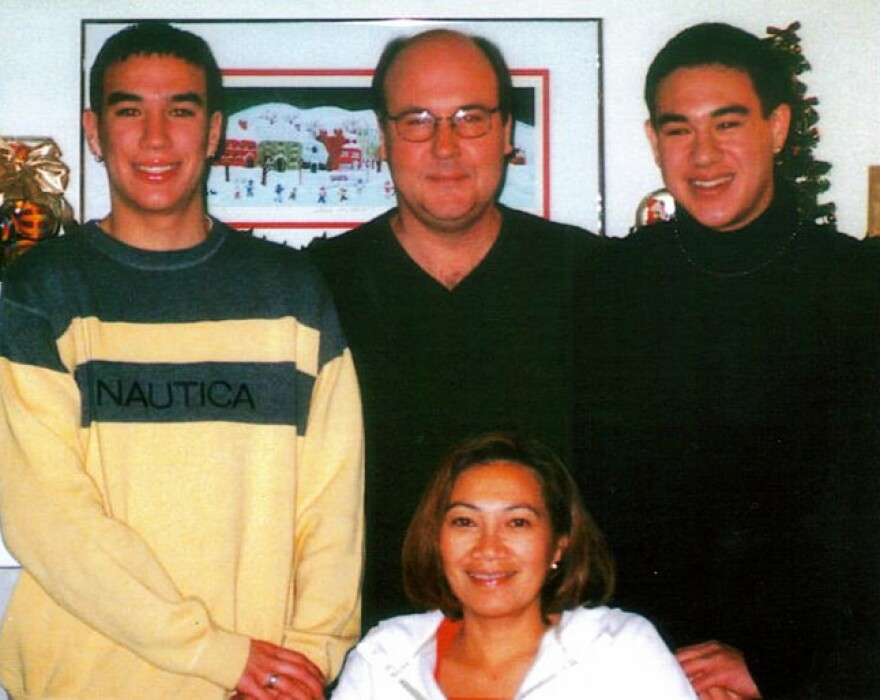

Kim says David was a popular kid who did well at his highly-rated public school He was an athlete, and a risk-taker, who flirted with drinking and smoking marijuana. But when he was 16, his parents were shocked to learn he was drinking heavily, abusing prescription sleeping pills and other drugs. After another six months of trying to manage David’s addiction on their own, Kim and his wife Marissa enrolled him in an outpatient program at Fairbanks, an addiction treatment center in Indianapolis.

Kim says that six months into the treatment program, things seemed to be going well for David. He continued to go to school. He was passing the drug tests his parents required him to take at home.

But it turned out David was finding a way to get high using computer dusting spray, which contains chemicals not detectable by normal drug screenings. One afternoon, he and a friend were huffing the spray in a pool at the friend’s parents’ house, because they’d read that using underwater would intensify the rush. The chemical stopped his heart. Though his friend pulled him out of the water and called an ambulance, David could not be revived.

When a person who has diabetes and gets treatment for it, if their blood sugar goes up or they eat something that they shouldn't, nobody looks at them as though they've got a moral failing in some way. Addiction is a chronic medical relapsing disease of the brain. It's not a weakness, not a moral failing.

Kim didn’t know it at the time, but David was still very early in the recovery process. “He was moving in the right direction. It was not his intention to lose his life,” says Kim. “It was simply that desire to get high was still really powerful.”

Kim and Marissa held Fairbanks at no fault in David’s death. In fact, they collaborated with Fairbanks on a documentary about David’s struggle, and founded a support group for parents of children with addiction.

From parent to patient

Despite his community work, Kim struggled to bear the pain of David’s death, and began to self-medicate. Two years later, he found himself drinking a quart of tequila and taking several days’ doses of Xanax each day.

When Marissa and their older son Josh found Kim nearly incoherent one night, he told them he wanted to go to Fairbanks.

“It was time for me to figure out how I had gotten to this point,” says Kim. “And it was clear to me that I didn't want to continue. I was very close to death, and I didn't want that.”

Kim’s illness was more advanced than David’s had ever been. After an evaluation, He was enrolled in an inpatient program and detoxed under medical supervision. For the first few days, he wandered from meeting to meeting in a fog.

Defining “higher power” on his own terms

Fairbanks embraced the 12-step system followed by Alcoholics Anonymous and taught widely across the country. Integral to this system is a belief in God, or a “higher power.” But Kim had been an agnostic for his whole adult life.

“So all of a sudden here I am in this environment myself, knowing I need to be there but seeing this required almost religious conversion,” Kim recalls.

On his fourth day in the inpatient program at Fairbanks, Kim attended a presentation where people early in recovery were sharing their stories. One man spoke about defining “higher power” according to your own understanding. Kim approached him, explained his backstory, and said he was struggling with the idea of a higher power.

“And he said ‘Why don't you make Dave part of your higher power so instead of a reason for him to drink and drug yourself to death he becomes a reason for you not to do that?’ And I said ‘I can do that?’ It was a revelation.’”

In his room at Fairbanks that night, Kim had what he describes as a spiritual experience, communicating with David’s spirit. “Dave became part of that higher power in that moment with me,” says Kim.

With that understanding, Kim became a model student of treatment, he says. Though he already knew many of the staff, as a patient, he felt even closer to them.

“All the staff reached out, they all understood and appreciated things,” he recalls. “It was just like they wrapped their arms around me. I felt as much as I could, given the situation. I felt welcomed, but not catered to. I was there for a reason.”

After a week in inpatient care, Kim completed six weeks in an outpatient program, also at Fairbanks.

Long-term recovery: a holistic approach

Kim says that he got more than he bargained for from his treatment experience. “I thought they were going to teach me how to stop using drugs and alcohol,” he says. “What they really did is they taught me how to live life, and deal with life in a totally different way.”

Kim says that after treatment, he began exercising more, worked on deepening his interpersonal relationships, and continued to cultivate his newfound spirituality, sometimes visiting mediums to facilitate communication with David.

While Kim has been sober now for 13 years, he still considers himself in long-term recovery. He attends seven recovery-related activities every week. He calls these 12- step meetings and other events his “medicine.” “It's what keeps me where I want to be as a person in long-term recovery from the disease of addiction,” Kim says.

Kim says he tells any doctor he sees that he’s a person in long-term recovery – so that they know not to prescribe him any habit-forming medications. He takes an anti-depressant, but he’s more sensitive than he was when he was taking Xanax.

“There's a phrase that I heard in recovery,” he says: "The good news is when you get into recovery you feel your feelings again. But that's also the bad news." He’s always been an emotional person, he says, but now his emotions are closer to the surface.

A mission to professionalize recovery

In 2006, Kim left his job in academia and began working full time in the field of addiction prevention, treatment and recovery. He has overseen grants for the State of Indiana, directed outreach at Fairbanks, and now heads the Indiana Addiction Issues Coalition, an advocacy group.

Along with many others in his field, Kim is working to fill a long-standing gap in addiction treatment: what happens after you leave.

“Historically treatment has been focused on the acute care end of things. But once we get them sort of stabilized, the recovery component has been relegated to 12-step groups – volunteers,” he says.

Kim says 12-step groups will continue to have a place in recovery. But his organization has a federal grant to train recovery coaches – a new kind of professional to help those in recovery with the skills and resources they need to avoid relapse.

It’s crucial to start seeing addiction as we see other chronic diseases, says Kim, and treating it as such. “When a person who has diabetes and gets treatment for it, if their blood sugar goes up or they eat something that they shouldn't, nobody looks at them as though they've got a moral failing in some way. Addiction is a chronic medical relapsing disease of the brain. It's not a weakness, not a moral failing.”

****

This narrative was compiled from a written submission by Kim Manlove and a phone conversation between Mr. Manlove and Side Effects reporter Andrea Muraskin. The narrative has not been fact-checked.