A depression treatment based on magnetic fields, not medications, appears to help many patients who don’t respond to other options.

But no one really knows what it does to the brain – or why it works for some people. Now, a University of Michigan Depression Center team will try to find out, with a new study that’s now open for certain depressed people to join.

The study will provide 25 daily transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) treatments to people who haven’t responded to antidepressants, and use an advanced brain scanner to look at how their brains respond.

Though everyone in the study will receive TMS therapy, some people will randomly receive an inactive treatment at first, to allow the researchers to see the difference between real response and placebo effect. Those who receive the inactive treatment have the option of a full course of 25 treatments after they complete the first phase of the study.

TMS therapy carries U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, and in the last year more insurance companies started covering it, though often with co-pays for each of the daily sessions during the recommended month-long treatment. Other insurers, not convinced that TMS works better than placebo, have held out.

The lack of understanding of how TMS actually affects the brain also frustrates psychiatrists like Stephan Taylor, M.D., the U-M professor who leads the new study.

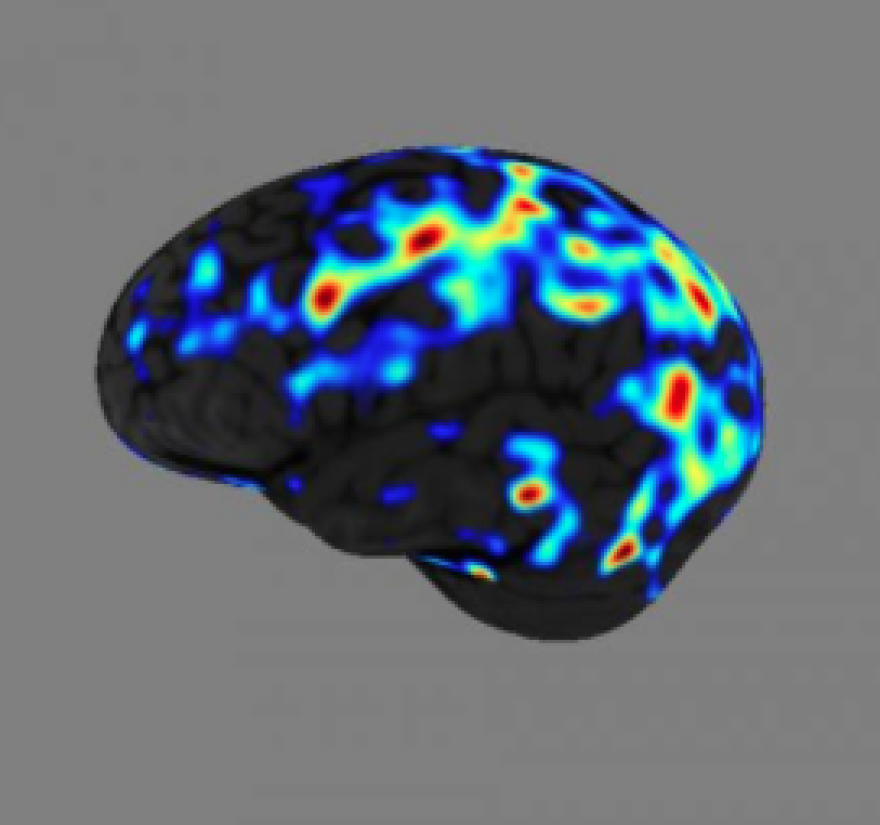

“Previous research suggests that TMS may restore balance between the executive functioning areas at the front of the brain, which govern things like concentration and planning, and the areas involved in emotional responses and negative thoughts,” he says. “We hope that by studying brain function in patients undergoing TMS, we can help explain what is going on, and perhaps illuminate why some patients experience remission after treatment. “

U-M is the only site in the country for the study, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health. The manufacturer of the TMS device also contributed funding as well as the device that will allow the researchers to deliver the inactive treatment, but is not involved in the study. Taylor and his team will use U-M’s Functional MRI Laboratory to scan participants’ brains before and after they complete TMS therapy.

Patients who have failed to respond to at least one antidepressant, and are still taking medication, may be candidates to participate if they meet other requirements. More information on the TMS study is available at http://umhealth.me/tms-study or by calling (734) 232-0129(734) 232-0129 or emailing psych-rtms-study@med.umich.edu.

The U-M Department of Psychiatry offers TMS therapy through its Neuromodulation Program, which also offers electroconvulsive therapy and vagus nerve stimulation. For more information visit http://www.psych.med.umich.edu/neuromodulation/

This article was originally published by the University of Michigan Health System on Aug. 11, 2014.