It had been a while since Stacey heard from her son, who’s incarcerated at Miami Correctional Facility in Bunker Hill, Indiana. They had an argument a few months ago, but she kept track of him through relatives who communicated with him more regularly, and even saved his voicemails so she could play them back whenever she missed him.

Then on Wednesday, Stacey’s son sent her a message: “I have covid love u.”

“I just started having a panic attack and bawling my eyes out,” says Stacey, who asked to be identified by her middle name for fear that prison staff would retaliate against her son. She worries he’s at higher risk from COVID-19 because of his hepatitis C.

“I couldn’t put any kind of thoughts together, so I just sent him a message back that said ‘I love you,’” she says. “If something happens to my son, I want him to know that I love him.”

After a stretch of slow growth, some Indiana prisons have experienced a surge in new coronavirus infections. Until recently, the Miami facility, which houses nearly 2,900 men, had reported that one person had tested positive and apparently died from the infection.

But the prison added another case in late August, and has seen a spike in September. The Indiana Department of Correction reports 69 new COVID-19 cases since last week out of 128 tests administered — a rate of 54%. Seven staff members have also tested positive since late last month.

Inmates and family members worry that the prison hasn’t taken adequate steps to prevent the spread of the virus. The increase in cases follows spikes at the New Castle and Putnamville prisons in August.

James Frye, spokesperson for the Miami facility, defended COVID-19 safety precautions at the prison. He declined to be interviewed for this story or to provide the prison’s specific testing protocols.

The agency has said repeatedly that it follows guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but that guidance leaves discretion to correctional facilities. It’s unclear how many untested prisoners at Miami or other prisons have contracted the disease; the corrections agency says 240 men are in quarantine or isolation at Miami.

Side Effects communicated with four women who have family members in the Miami facility and read messages from some of the men incarcerated there. They all expressed concerns about the prison’s safety measures during the pandemic.

Stacey’s son wrote again on Wednesday that after two inmates in his dorm tested positive, he was moved into their cell “without sanitizing or disinfecting it, and now I have [COVID-19].” He said his liver hurt, and he had lost consciousness twice.

The four women say that correctional officers, along with support personnel called in from the National Guard, don’t always wear masks properly, even though inmates can be written up if they’re caught without a mask on.

“Up until this point, they have not made the COs wear their masks,” says Teresa, who asked to be identified only by her first name. Her son is in the Miami prison.

When prisoners ask officers to put the masks on, “they’ll just do like a fake cough,” says another woman.

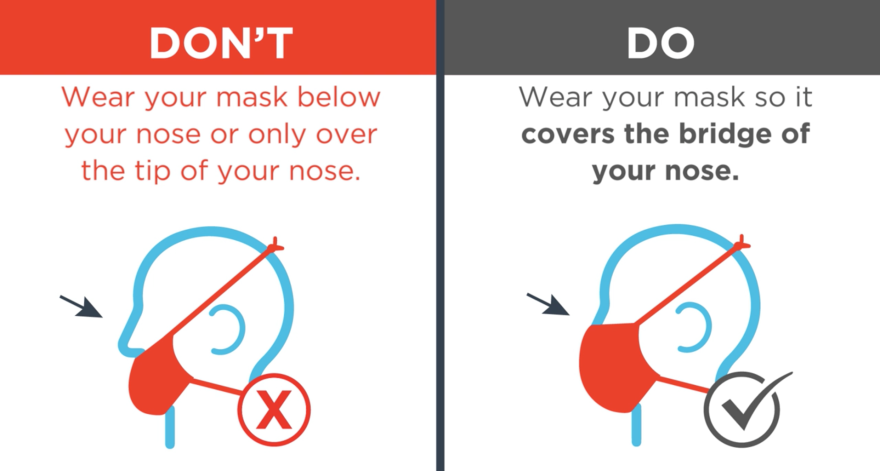

On Aug. 28, the prison posted a photo on Facebook that showed a correctional officer with a mask under his nose. A few days later, the prison shared a post demonstrating that masks should cover the nose.

Teresa and others speculate that the outbreak occurred because of a failure to follow CDC guidelines on masks — especially during a recent sweep for contraband.

“It was pulled down under their nose, and some had it around their neck,” says Teresa. “I was just livid when I found out. All of a sudden they’re having an outbreak, and you can connect the dots to when they came in.”

Frye, the Miami spokesperson, wrote in an email that staffers are screened prior to entry and wear masks inside the prison. If they have a temperature or other COVID-19 symptoms, they are not allowed to work, he wrote.

Even with the recent cases, the men inside and the women say the prison has been slow to act to curb the spread of the virus.

“They just came in last night and took everyone’s temperature,” one prisoner wrote to his wife on Tuesday, though the facility had reported a new case the week before.

“They’re not letting us clean our cells,” the man wrote. “They haven’t come to spray bleach since this new wave of the corona started.” He also said that under the recent lockdown, when prisoner movement is restricted, inmates are only allowed to shower every three days.

Teresa and one of the prisoners say men at the Miami prison are mostly fed sack meals, which have become even less tolerable during lockdown. “On a number of occasions my meal is completely inedible due to spoilage,” one prisoner wrote. “The staff keeps moving on without listening to any complaints.”

"Spoiled food is not intentionally provided to any offender," Frye wrote in his email. "In the rare case this should happen, the meal would be replaced when brought to the attention of the server."

Advocates have called for Gov. Eric Holcomb to release certain groups of inmates, such as the elderly or those close to their scheduled release date, to mitigate the spread of the virus in prisons. Holcomb has declined to do so.

In the second message Stacey received from her son, he indicated he wasn’t sure when he’d be able to write again. Stacey called the prison on Thursday to find out more information, but hasn’t heard back.

“So I gotta wait ... to find out if my son survives this? That is absolutely ridiculous,” she says. “I am so terrified.”

On Thursday afternoon, the women reported that the prison shut off the inmates’ internet access. The expected calls from their loved ones never came, and the women weren’t sure when communications would start again.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health. Jake Harper can be reached at jharper@wfyi.org. He's on Twitter @jkhrpr.