On a rainy day in Austin, Indiana, Brittany Combs, the public health nurse for Scott County, drives around in a white SUV. Medical supplies are piled high in the back of the vehicle: syringes and condoms, containers for used needles, over-the-counter medications.

Combs stops to ask a woman if she needs any syringes. The woman doesn’t need any today. She’s quitting. “She said she’s taking something for withdrawals three times a day,” Combs said. “She looks better now than she has in months.”

This is what Combs wants to happen — for people to stop using heroin and other injection drugs. She regularly offers them information about getting into treatment. For those who aren’t ready, Combs is there to hand out sterile syringes so people don’t share dirty ones. She knows what happens if they do.

Almost three years ago, Scott County was hit with one of the worst HIV outbreaks in recent history, with 223 diagnosed cases to date. The disease was spread primarily by injection drug use.

Many Indiana communities, including Marion County, have their own injection drug use problem. And, since the state legalized county-based syringe exchanges in 2015, eight other counties have started or made plans to start their own exchanges to prevent the spread of diseases such as hepatitis C and HIV.

Marion County, home to Indianapolis and the state’s largest population center, is not one of them, but some public health experts think it should be.

Dr. Virginia Caine, the director of the Marion County health department, said she plans to bring a proposal to the city-county council in October.

"We have to really look at this very carefully and say that, you know, this city might benefit from a syringe exchange program,” she said.

Caine mentioned other cities in the region such as Chicago, Louisville and Cincinnati already have syringe exchanges.

And Carrie Lawrence, co-director of the Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention, points out that smaller Indiana communities, with fewer resources have pulled ahead of Marion county.

“It was actually surprising that Marion County was not one of the first to implement a syringe exchange,” she said.

A big population with growing drug use

The same factors that led to the Scott County outbreak could result in a similar problem in Indianapolis, said Brad Ray, a researcher at Indiana University’s School of Public and Environmental Affairs in Indianapolis.

“Think about the population of Scott County compared to the population here,” he said. Scott County’s outbreak was mostly centered in Austin, a town of about 4,200 people. Indianapolis has a population of 864,000.

HIV could be spreading right now, and public health officials might not even know about it. “We could be sitting on top of a huge epidemic,” Ray said.

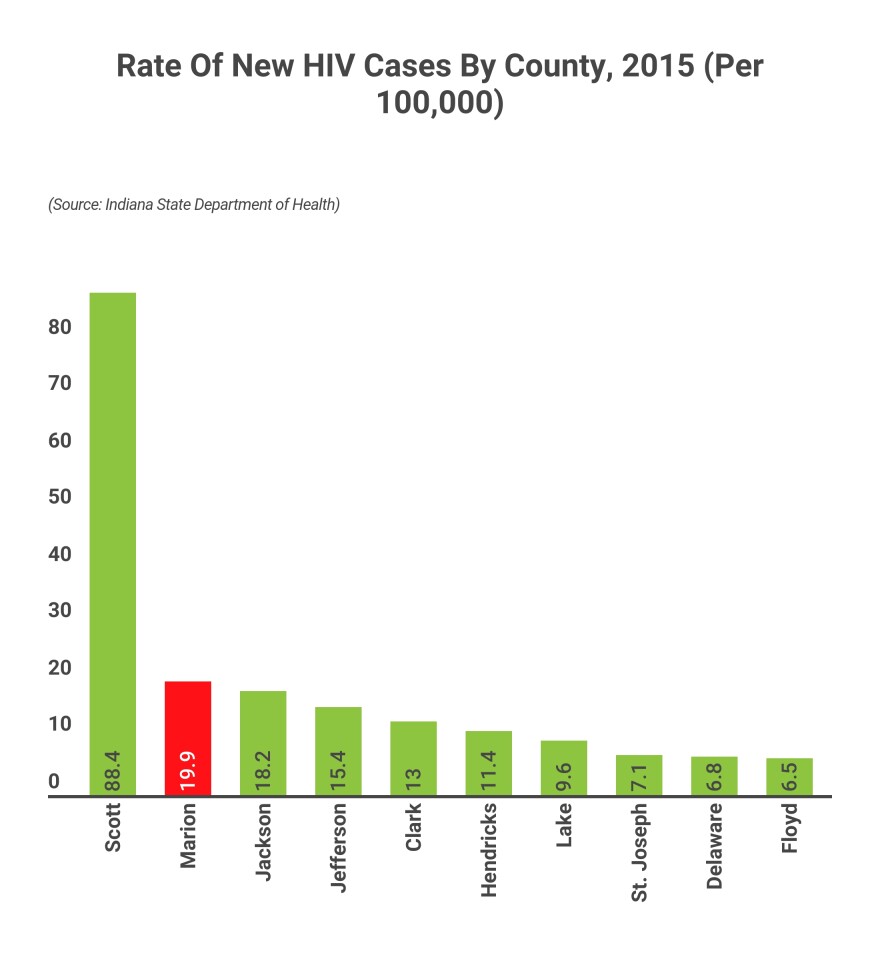

Marion County had the second- highest rate per capita of new HIV cases in 2015. Prior to Scott County’s outbreak, Marion consistently outpaced all other counties in its rate of new infections.

And while the number of new HIV infections has remained stable over the last few years, the rate at which people report that their infections came from injection drug increased between 2014 and 2016. In 2016, there were 14 new cases of HIV attributed to injection drug use, according to the county health department.

The real numbers may be larger, Ray said, in part because people who use injection drugs don’t go to the doctor very often.

“Many of these individuals aren’t getting tested. These are people that potentially don't know their HIV status,” he said.

That would make it easy for HIV to hide in the drug-using population.

Meanwhile, Ray said, injection drug use is on the rise. It’s difficult to measure the number of people in a community who use drugs, but the number of overdoses is an indicator.

“We are seeing huge increases in illicit opiate deaths,” Ray said.

Public health researchers also cite the rate of soft tissue infections, which are often caused by using dirty needles, and the number of new hepatitis C infections. Both of those have gone up dramatically in Marion County in the last few years. Between 2011 and 2015, the rate of soft tissue infections associated with injection drug use more than doubled. And there were 30 new cases of hepatitis C reported in 2016, compared to 7 in 2013. The health department is projecting 64 new cases in 2017.

Growing rates of costly diseases

Eighty percent of people newly infected with hepatitis C report using injection drugs. In that environment, health experts say a syringe exchange is vital to prevent disease from spreading.

“Those numbers should be terrifying for the city and the county and the state,” said Dr. Krista Brucker, an emergency doctor at Eskenazi Hospital. She treats patients who have overdosed, and offers to test them for hepatitis C.

HIV gets a lot of attention, but Brucker said hepatitis C is a problem on its own. The infection can lead to liver damage and cancer, and the cure costs tens of thousands of dollars per case.

“This is a completely preventable disease. It’s not a mystery how you do it, it’s not expensive to do it,” she said.

The solution, she said, is a syringe exchange, and the data Brucker is gathering from drug users coming through her ER could help make the case that Marion County needs one.

Carrie Lawrence said it’s not just about the human costs — a syringe exchange program could also save money.

“We know a lifetime of HIV care is upwards of $400,000 each,” she said.

If the 223 people infected in the Scott County outbreak receive treatment, that would put the cost at around $90 million. That doesn’t include the costs associated with treating or curing hepatitis C.

Caine could face pushback when she presents to the city-county council next month. One of the common arguments against needle exchanges is that they increase drug use by making needles more accessible. It’s a concern sometimes voiced by law enforcement, including Indiana’s attorney general, Curtis Hill, though Caine indicated the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department is open to the conversation.

However, there’s no evidence supporting the claim the programs increase drug use, Caine said. “The people who participate in these syringe exchange programs, they are five times more likely to get into a drug treatment program,” she said.

That statistic comes from a study out of Seattle, but Brittany Combs, has seen that work firsthand down in Scott County.

“We have lots and lots of people that have dropped out of the program because they’re in rehab, and we’re the ones that helped them get in there,” she said.

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a reporting collaborative focused on public health.