People with hepatitis C who sought prescriptions for highly effective but pricey new drugs were significantly more likely to get turned down if they had Medicaid coverage than if they were insured by Medicare or private commercial policies, a recent study found.

This story was originally published by Kaiser Health News, a nonprofit national health policy news service.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine analyzed the hepatitis C prescriptions from 2,342 patients in Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey that were submitted between November 2014 and April 2015 to a large specialty pharmacy that serves the region.

The drugs included Sovaldi, Harvoni and Viekira Pak, and others that are part of the treatment regimen. A 12-week course of treatment for one patient can reach more than $90,000.

The new drugs generally cure the disease in nine out of 10 cases, without the serious side effects that made many people forgo treatment in the past. But because of their hefty price tag, insurers often restrict access by limiting the availability to people whose livers show serious signs of damage, among other criteria.

Overall, insurers denied 16 percent of prescriptions for the drugs. (The figure incorporates the results of appeals that were filed after initial denials.) The proportion of Medicaid denials, however, was much higher: 46 percent.

In contrast, only 10 percent of patients with private insurance and 5 percent of Medicare patients were denied the drugs.

The results were presented this week at the 2015 meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“Our hypothesis was that Medicaid patients would be more likely to receive absolute denials,” says Dr. Vincent Lo Re III, an assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at Penn, referring to denials that incorporated appeals. “But I was surprised by the magnitude.”

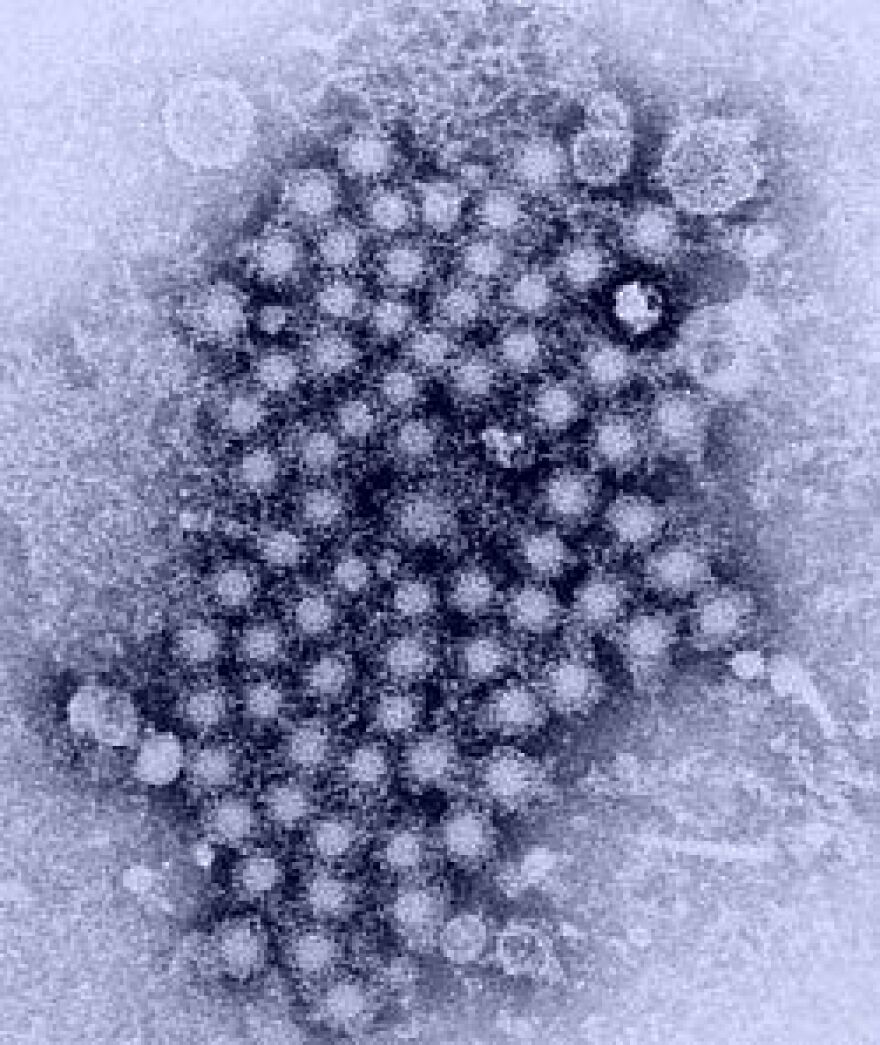

An estimated 2.7 million people in the United States are infected with hepatitis C, a viral liver infection that can lead to cirrhosis, or scarring, of the liver, liver cancer and death. The infection is often spread today by sharing needles to inject drugs, but many people have undetected disease because they were infected years ago through contact with infected blood before the virus was discovered or blood donations were screened for it.

A study published in August in the Annals of Internal Medicine examined Medicaid reimbursement criteria in 42 states for Sovaldi. It found that three quarters of those states limited access to people with advanced liver disease and half required people to be drug or alcohol-free for a period of time before Hepatitis C drug prescriptions could be filled.